Image 1 of 4

Image 1 of 4

Image 2 of 4

Image 2 of 4

Image 3 of 4

Image 3 of 4

Image 4 of 4

Image 4 of 4

Erskine Nicol R.S.A., A.R.A. 1825-1904

SOLD

Always Tell the Truth

Oil on canvas, 132 x 104.5 cm.

Signed and dated 1874, lower-right

Exhibited: Royal Academy, 1875, no. 561

Engraved: by William Henry Simmons and published by Pilgeram & Lefèvre, London, 1876

When Vincent Van Gogh discovered the work of Scottish painter Erskine Nicol (1825–1904), he was so fascinated with it that he wrote to his brother Theo: ‘I saw a new engraving after Erskine Nicol, Sabbath, an old woman going home in the rain; it is very fine and well engraved’.1 These words were written in Amsterdam in 1877, when this engraving was published in London and in Washington DC by Lefèvre and Schaus. These editors had hired one of Nicol’s favourite engravers, William Henry Simmons, to reproduce the original, a large oil from 1875. So, Van Gogh’s sentence hints at the impact that engravings were likely to have in the art world and on his own production. The ‘old woman’ admired by Van Gogh in Sabbath Day, was actually the same as the grandmother depicted in Always Tell the Truth. Interestingly, these artworks were listed among Nicol’s ‘principal pictures’ in 1895.2 But why is this portrait of a grandmother still so striking today?

The grandmother’s face is a study of old age, reminding viewers of Rembrandt’s tronies, or depictions of specific physiognomies. Her wrinkled face, little round eyes and characteristic chin make us feel that a real individual is portrayed here. In fact, she is recognised in many pictures by Nicol. She makes a discreet appearance in The Doubtful Sixpence (1873), in which she is seen from the back. Then, her full portrait is drawn in Old Woman holding an open Umbrella, a small panel from 1874 and frontal view of this lady walking under the rain. In Auld Lang Syne (1875), she sadly ponders over the letter that she has just read. Then, she faces bad weather again in Lonely Tenant of the Glen (or The Faggot Gatherer, an oil on canvas from 1878). Under sunnier circumstances, she unfolds a beige shawl in front of a man on his threshold in Aw Ae Woo, a watercolour from 1884. Finally, she is also presented in her home, reading the bible in Sunday Morning (1876), or caring for her sick daughter in Her ain Bairn (1887). These are but a few examples of a long list of artworks bearing witness to the long-lasting relationship between the artist and this model, who might have been a relative or even a professional model, as she also sat for Nicol’s friend, Thomas Faed, and his picture called When the Day is Done (1870). In this artwork too, the model wears the paisley shawl which Nicol painted so meticulously in Always tell the Truth. This prop participates in the visual construction of the model’s Scottish identity, because it was made in Scotland and was often a treasured gift, just like the Glengarry bonnet worn by the boy. It also suggests that the picture might have been painted in Pitlochry, where the painter had turned a disused church into his studio in the 1870s.

At that time, the model’s nationality was noticed by all art critics, such as Wilfrid Meynell,3 or the journalist writing for the Illustrated London News, who claimed: ‘Always Tell the Truth shows an ancient Scotch dame admonishing a […] bairnie’. The journalist also insisted that the picture put forward Nicol’s belonging to the ‘same school’ as ‘William Quiller Orchardson’ and ‘John Phillip’,4 that is to say the Scottish school specialising in genre painting.5 Both in style and subject, the picture is indeed typically Scottish.

This was also the opinion of Henry Blackburn, who commented on the ‘characteristic white bonnet with black ribbon’ worn by the ‘old Scotchwoman’.6 Blackburn had seen the picture in 1875 at the Royal Academy in London (n°561), where Nicol also had The Sabbath Day (n°1125) and The New Vintage (n°245) that year, prompting the columnist for The Academy to declare that such pictures were ‘strongly painted’ and marked by ‘vigour’.7 These expressions allude to the heavy impasto, but also vivid colours of Always tell the Truth, such as the bright red of the flax, the blue of the grandmother’s shirt, or the ochre yellow of her shawl, deemed ‘peculiarly rich and brilliant’ by the columnist for The Athenaeum. He also insisted that ‘this garment supplied an important, indeed, the chief element of the chiaroscuro of the picture’.8

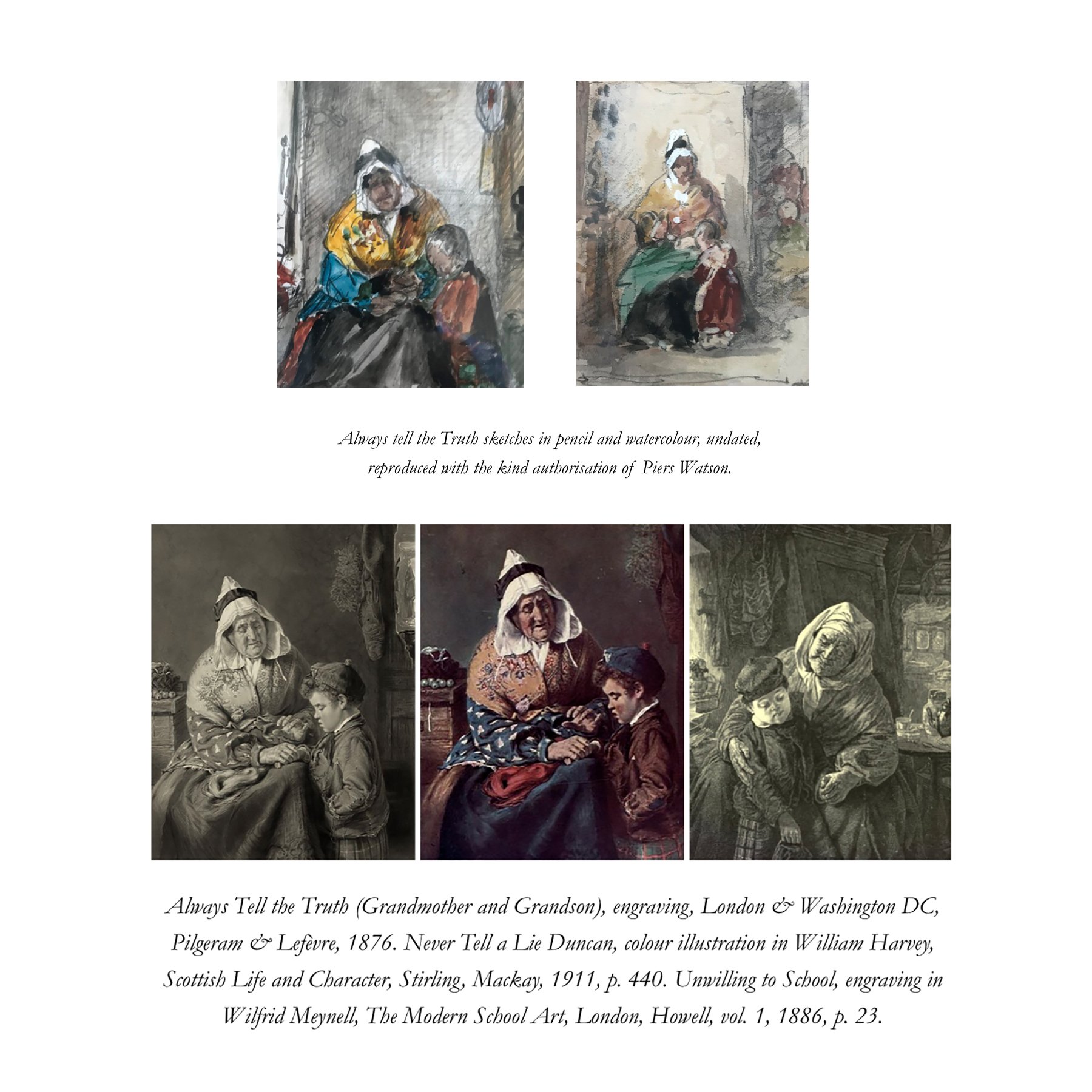

Two preparatory sketches (illustrated) indicate that Nicol created this picture with a sense of colour on his mind, and that the Scottish symbols of the shawl, white headdress and Tam O’Shanter hanging in the background were important elements, as they already appear there. These studies also reveal that Nicol had considered painting this scene as a three-quarter view, or as a full-length portrait with secondary characters in the background. It was eventually the three-quarter length which prevailed for the finished picture, which is more than a metre high. Nicol painted smaller versions though, especially an oil on canvas of 60 x 50 cm, made in 1875 with modifications in details and colours. A third version, with the addition of a ‘grandfather’ who ‘looks on and listens with approval to the moral law which his good wife is endeavouring to inculcate’, travelled to America and was sold there in 1891.9

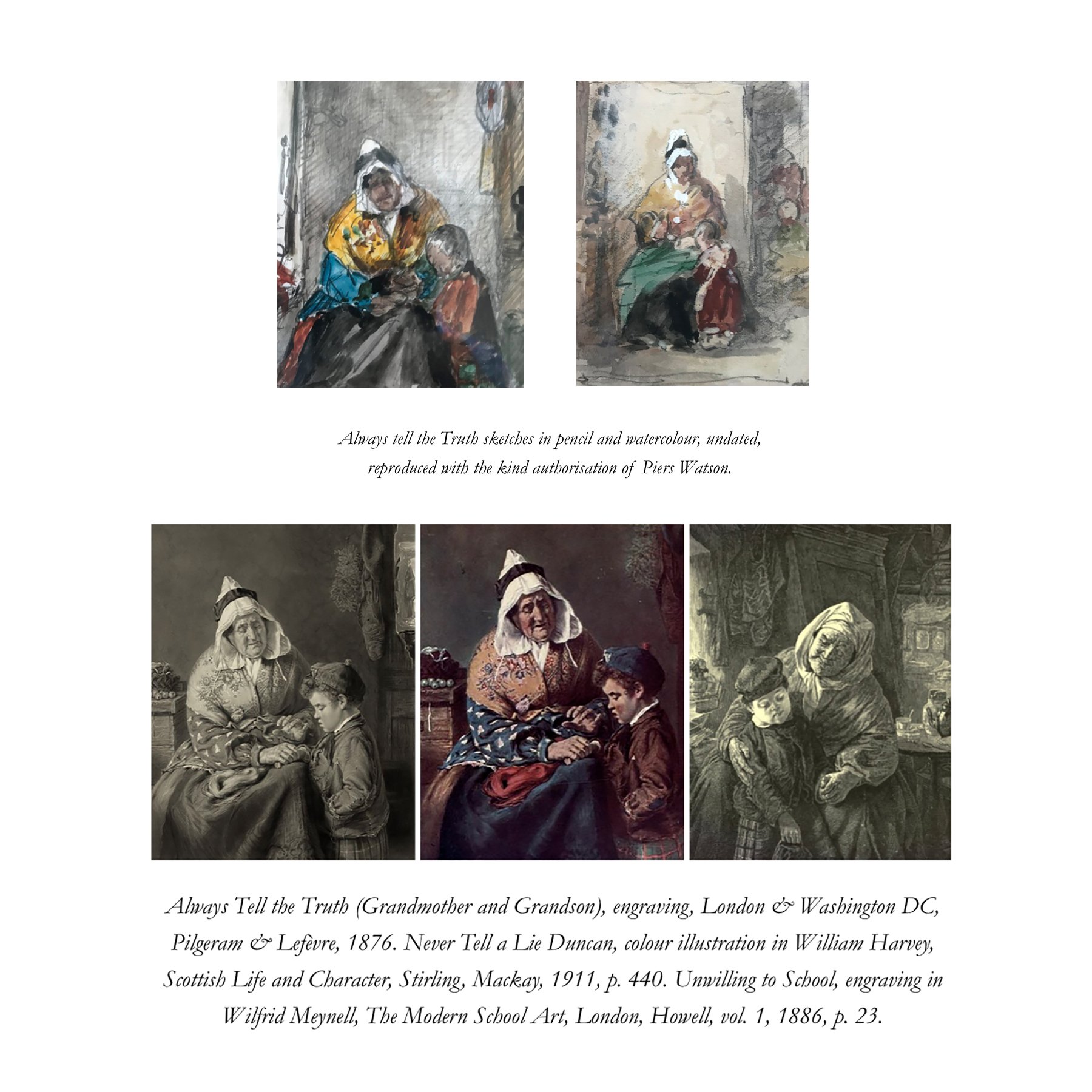

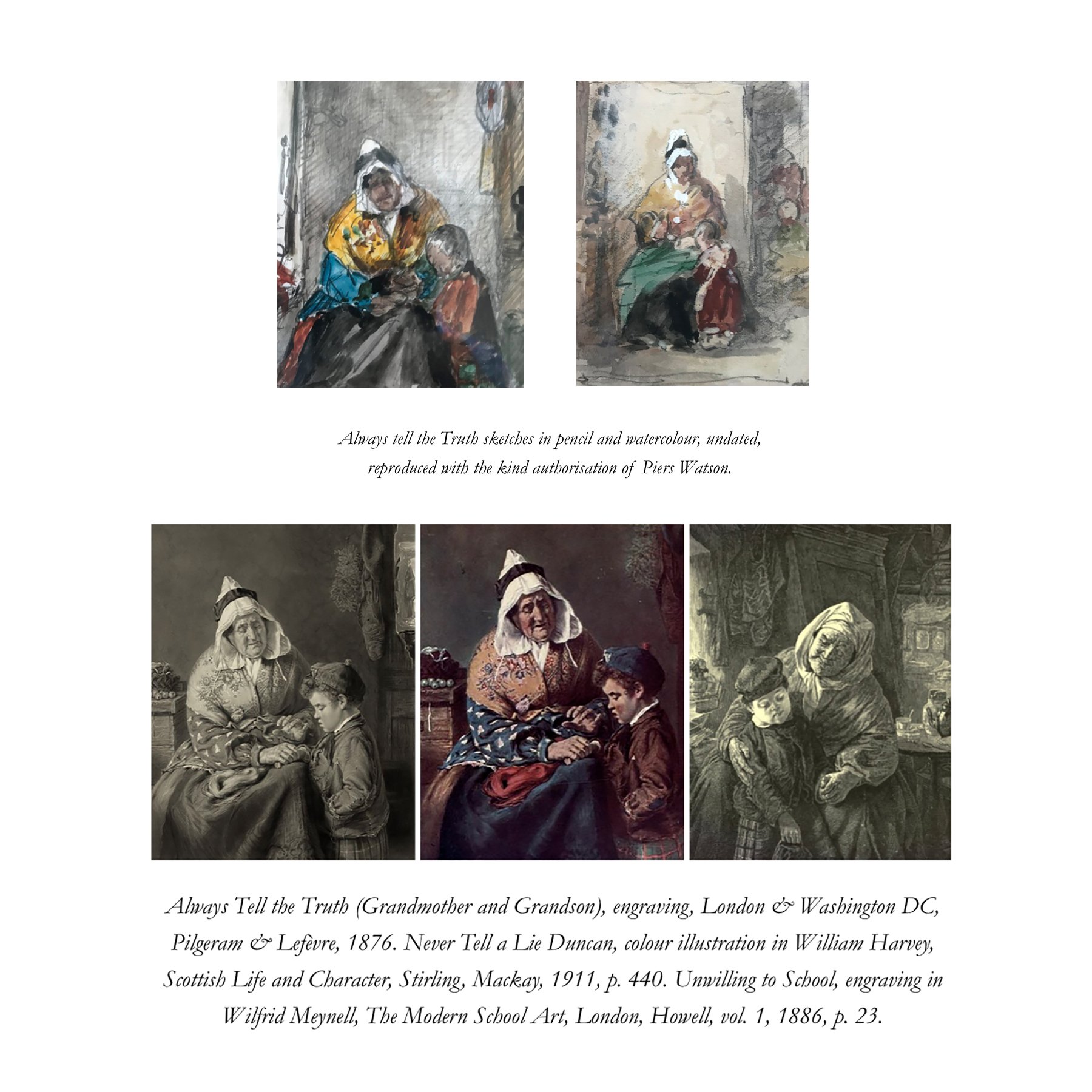

It was the destiny of this popular picture to circulate around the world and to survive centuries thanks to its different forms. Pilgeram & Lefèvre bought its copyright and had it engraved by William Henry Simmons (illustrated), in order to print it in 1876 in London and Washington DC. Thus, this scene was reproduced by the thousand and the success of these copies is witnessed by the fact that a year later, these publishers commissioned the same engraver to reproduce Sabbath Day. This was how the humblest buyers could collect such images, as was the case of Vincent van Gogh. Later on, Always tell the Truth was even turned into a colour illustration in the book Scottish Life and Character, by William Harvey. But this illustration was rechristened Never tell a Lie Duncan (1911). The new title gave a name to the grandson and further emphasised his Scottishness, even if his clothes already left no doubt as to his nationality. His kilt became even more obvious in Unwilling to School, in which the two familiar figures were portrayed again by Nicol, who thus continued telling their story for the next Royal Academy Exhibition, in 1876. This three-quarter view of the grandmother comforting her grandchild about to leave for school, with his bundle in his hand, was engraved for Wilfrid Meynell’s Modern School of Art (London, 1886).

So, the picture presented at the Gorry Gallery seems to be the first of a successful series of images which would become emblems of Scottish rural life. It is probably the original and largest of the oil versions, allowing viewers to fully admire the mastery with which details, such as the flower motifs on the shawl, were painted. This is a highly finished picture, a quality which was valued by Victorians, hence its popularity when it was exhibited in 1875.

Similarly, the expressions of the two characters are beautifully painted. It is Nicol’s talent in drawing emotions which often struck art lovers, and which accounts for his election as a Royal Scottish Academician in 1859, and then as an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1866. The reasons for Nicol’s reputation are fully visible here: his scene captures the very moment when a grandmother, who was spinning flax with a handheld distaff, realises that her grandson has stolen one of the green apples standing on the furniture next to her, where six other fruit, as well as her basket with spinning material, are carefully painted. She has tucked her distaff under her arm to gently hold the right hand of the boy and talk to him. The placement of the hands expresses all the tenderness that the grandmother feels for the boy. Their gestures are particularly delicate here and are redolent of biblical imagery.

The scene is evocative of Christian values, which were dear to Victorians. ‘Thou shalt not steal’ or ‘Thou shalt not lie’, teaches the grandmother; and the little boy looks down in shame, with red cheeks indicating that he will not be caught in such mischief again. His expression of candour mixed with regret tells the eternal story of the apple of temptation, but also of education, transmission, and family relationships. Today like yesterday, it is likely to strike a chord with all parents.

Dr Amélie Dochy-Jacquard

1. Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Amsterdam, 25 Nov. 1877, in Robert Harrison, ed., The Complete Letters of Vincent Van Gogh, Boston, Bulfinch, 1991, 3 vols., vol. 1, n°114. See also Robert Verhoogt, Art in Reproduction, Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, 2007, p. 520.

2. George Washington Moon, ed., Men and Women of the Time, A Dictionary of Contemporaries, London, Routledge, 1895, pp. 627-628.

3. Wilfrid Meynell, The Modern School of Art, London, Howell, 1886, pp. 23–5.

4. ‘Exhibition of the Royal Academy’, Illustrated London News, 8 May 1875, p. 445.

5. Amélie Dochy, ‘A Scottish Art and Heart: The Transparent Influence of the Scottish School of Art on Erskine Nicol's Depictions of Ireland’, Études écossaises, vol. 16, 2013, pp. 119–40.

6. Henry Blackburn, Academy Notes, London, Chatto & Windus, 1875, p. 39.

7. ‘The Royal Academy Exhibition’, The Academy, London, 5 Jun. 1875, p. 591.

8. ‘New Engravings’, The Athenaeum, 17 Feb. 1877, p. 231.

9. This version, also called Always tell the Truth, was also of cabinet size (60 x 50 cm), and was in the collection of George I. Seney. Art Sales, New York, American Art Galleries, 1891, p. 245.

SOLD

Always Tell the Truth

Oil on canvas, 132 x 104.5 cm.

Signed and dated 1874, lower-right

Exhibited: Royal Academy, 1875, no. 561

Engraved: by William Henry Simmons and published by Pilgeram & Lefèvre, London, 1876

When Vincent Van Gogh discovered the work of Scottish painter Erskine Nicol (1825–1904), he was so fascinated with it that he wrote to his brother Theo: ‘I saw a new engraving after Erskine Nicol, Sabbath, an old woman going home in the rain; it is very fine and well engraved’.1 These words were written in Amsterdam in 1877, when this engraving was published in London and in Washington DC by Lefèvre and Schaus. These editors had hired one of Nicol’s favourite engravers, William Henry Simmons, to reproduce the original, a large oil from 1875. So, Van Gogh’s sentence hints at the impact that engravings were likely to have in the art world and on his own production. The ‘old woman’ admired by Van Gogh in Sabbath Day, was actually the same as the grandmother depicted in Always Tell the Truth. Interestingly, these artworks were listed among Nicol’s ‘principal pictures’ in 1895.2 But why is this portrait of a grandmother still so striking today?

The grandmother’s face is a study of old age, reminding viewers of Rembrandt’s tronies, or depictions of specific physiognomies. Her wrinkled face, little round eyes and characteristic chin make us feel that a real individual is portrayed here. In fact, she is recognised in many pictures by Nicol. She makes a discreet appearance in The Doubtful Sixpence (1873), in which she is seen from the back. Then, her full portrait is drawn in Old Woman holding an open Umbrella, a small panel from 1874 and frontal view of this lady walking under the rain. In Auld Lang Syne (1875), she sadly ponders over the letter that she has just read. Then, she faces bad weather again in Lonely Tenant of the Glen (or The Faggot Gatherer, an oil on canvas from 1878). Under sunnier circumstances, she unfolds a beige shawl in front of a man on his threshold in Aw Ae Woo, a watercolour from 1884. Finally, she is also presented in her home, reading the bible in Sunday Morning (1876), or caring for her sick daughter in Her ain Bairn (1887). These are but a few examples of a long list of artworks bearing witness to the long-lasting relationship between the artist and this model, who might have been a relative or even a professional model, as she also sat for Nicol’s friend, Thomas Faed, and his picture called When the Day is Done (1870). In this artwork too, the model wears the paisley shawl which Nicol painted so meticulously in Always tell the Truth. This prop participates in the visual construction of the model’s Scottish identity, because it was made in Scotland and was often a treasured gift, just like the Glengarry bonnet worn by the boy. It also suggests that the picture might have been painted in Pitlochry, where the painter had turned a disused church into his studio in the 1870s.

At that time, the model’s nationality was noticed by all art critics, such as Wilfrid Meynell,3 or the journalist writing for the Illustrated London News, who claimed: ‘Always Tell the Truth shows an ancient Scotch dame admonishing a […] bairnie’. The journalist also insisted that the picture put forward Nicol’s belonging to the ‘same school’ as ‘William Quiller Orchardson’ and ‘John Phillip’,4 that is to say the Scottish school specialising in genre painting.5 Both in style and subject, the picture is indeed typically Scottish.

This was also the opinion of Henry Blackburn, who commented on the ‘characteristic white bonnet with black ribbon’ worn by the ‘old Scotchwoman’.6 Blackburn had seen the picture in 1875 at the Royal Academy in London (n°561), where Nicol also had The Sabbath Day (n°1125) and The New Vintage (n°245) that year, prompting the columnist for The Academy to declare that such pictures were ‘strongly painted’ and marked by ‘vigour’.7 These expressions allude to the heavy impasto, but also vivid colours of Always tell the Truth, such as the bright red of the flax, the blue of the grandmother’s shirt, or the ochre yellow of her shawl, deemed ‘peculiarly rich and brilliant’ by the columnist for The Athenaeum. He also insisted that ‘this garment supplied an important, indeed, the chief element of the chiaroscuro of the picture’.8

Two preparatory sketches (illustrated) indicate that Nicol created this picture with a sense of colour on his mind, and that the Scottish symbols of the shawl, white headdress and Tam O’Shanter hanging in the background were important elements, as they already appear there. These studies also reveal that Nicol had considered painting this scene as a three-quarter view, or as a full-length portrait with secondary characters in the background. It was eventually the three-quarter length which prevailed for the finished picture, which is more than a metre high. Nicol painted smaller versions though, especially an oil on canvas of 60 x 50 cm, made in 1875 with modifications in details and colours. A third version, with the addition of a ‘grandfather’ who ‘looks on and listens with approval to the moral law which his good wife is endeavouring to inculcate’, travelled to America and was sold there in 1891.9

It was the destiny of this popular picture to circulate around the world and to survive centuries thanks to its different forms. Pilgeram & Lefèvre bought its copyright and had it engraved by William Henry Simmons (illustrated), in order to print it in 1876 in London and Washington DC. Thus, this scene was reproduced by the thousand and the success of these copies is witnessed by the fact that a year later, these publishers commissioned the same engraver to reproduce Sabbath Day. This was how the humblest buyers could collect such images, as was the case of Vincent van Gogh. Later on, Always tell the Truth was even turned into a colour illustration in the book Scottish Life and Character, by William Harvey. But this illustration was rechristened Never tell a Lie Duncan (1911). The new title gave a name to the grandson and further emphasised his Scottishness, even if his clothes already left no doubt as to his nationality. His kilt became even more obvious in Unwilling to School, in which the two familiar figures were portrayed again by Nicol, who thus continued telling their story for the next Royal Academy Exhibition, in 1876. This three-quarter view of the grandmother comforting her grandchild about to leave for school, with his bundle in his hand, was engraved for Wilfrid Meynell’s Modern School of Art (London, 1886).

So, the picture presented at the Gorry Gallery seems to be the first of a successful series of images which would become emblems of Scottish rural life. It is probably the original and largest of the oil versions, allowing viewers to fully admire the mastery with which details, such as the flower motifs on the shawl, were painted. This is a highly finished picture, a quality which was valued by Victorians, hence its popularity when it was exhibited in 1875.

Similarly, the expressions of the two characters are beautifully painted. It is Nicol’s talent in drawing emotions which often struck art lovers, and which accounts for his election as a Royal Scottish Academician in 1859, and then as an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1866. The reasons for Nicol’s reputation are fully visible here: his scene captures the very moment when a grandmother, who was spinning flax with a handheld distaff, realises that her grandson has stolen one of the green apples standing on the furniture next to her, where six other fruit, as well as her basket with spinning material, are carefully painted. She has tucked her distaff under her arm to gently hold the right hand of the boy and talk to him. The placement of the hands expresses all the tenderness that the grandmother feels for the boy. Their gestures are particularly delicate here and are redolent of biblical imagery.

The scene is evocative of Christian values, which were dear to Victorians. ‘Thou shalt not steal’ or ‘Thou shalt not lie’, teaches the grandmother; and the little boy looks down in shame, with red cheeks indicating that he will not be caught in such mischief again. His expression of candour mixed with regret tells the eternal story of the apple of temptation, but also of education, transmission, and family relationships. Today like yesterday, it is likely to strike a chord with all parents.

Dr Amélie Dochy-Jacquard

1. Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Amsterdam, 25 Nov. 1877, in Robert Harrison, ed., The Complete Letters of Vincent Van Gogh, Boston, Bulfinch, 1991, 3 vols., vol. 1, n°114. See also Robert Verhoogt, Art in Reproduction, Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, 2007, p. 520.

2. George Washington Moon, ed., Men and Women of the Time, A Dictionary of Contemporaries, London, Routledge, 1895, pp. 627-628.

3. Wilfrid Meynell, The Modern School of Art, London, Howell, 1886, pp. 23–5.

4. ‘Exhibition of the Royal Academy’, Illustrated London News, 8 May 1875, p. 445.

5. Amélie Dochy, ‘A Scottish Art and Heart: The Transparent Influence of the Scottish School of Art on Erskine Nicol's Depictions of Ireland’, Études écossaises, vol. 16, 2013, pp. 119–40.

6. Henry Blackburn, Academy Notes, London, Chatto & Windus, 1875, p. 39.

7. ‘The Royal Academy Exhibition’, The Academy, London, 5 Jun. 1875, p. 591.

8. ‘New Engravings’, The Athenaeum, 17 Feb. 1877, p. 231.

9. This version, also called Always tell the Truth, was also of cabinet size (60 x 50 cm), and was in the collection of George I. Seney. Art Sales, New York, American Art Galleries, 1891, p. 245.